- October 22, 2020

- 1:17 am

- No Comments

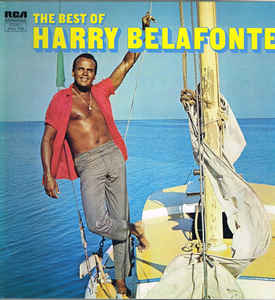

A PERSONAL TRIBUTE TO HARRY BELAFONTE

Jaw Jaw Jawing By:

supportadmin_Qhh2

(Jaw jaw jawing – Alex Pascall OBE)

It was the revelation that the COVID-19 pandemic disproportionately afflicted the African-Caribbean population that my wife Joyce alerted me to what British Prime Minister Lloyd George stated about the West Indies being ‘The slum of the Empire”. In observing this plight I decided to review other passages braved in the 20th Century whilst resisting physical attacks, segregation, racism, inequality and the ills of British legislation and Colonisation on Caribbean’s of the British Commonwealth.

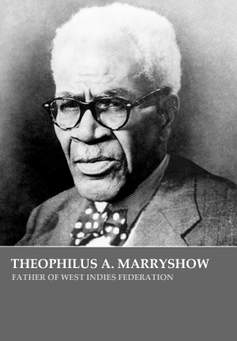

The name of the Jamaican Marcus Garvey is fairly well known to already enlightened members of the globe interested in the achievements of the peoples of the Diaspora. Their admiration of him is echoed in poetry and musical compositions that reference society. It is in Britain I got to know of the advances he made and the challenges he met, as Caribbean history was not part of Caribbean curriculum when I was at school. For those of us from the Southern Caribbean we speak too of other visionaries such as Theophilus Albert Marrishow, ‘Father of the Federation” of the West Indies a similar entity to the familiar, European Union (EU).

The Federation was an attempt to forge a single nation out of the disparate territories of the British West Indies. It offered hope, in my lifetime, of an escape from the claws of British Colonisation and a beacon of hope for Caribbean advancement in the arts, industry and commerce.

Sadly, the union came to a crunching halt in 1962 and subsequently, it took quite a while for the historical contributions Black people have made as intellectuals, inventors, Prime Ministers, distinguished members of the medical and law fraternities, servicemen and women during World Wars 1 and 2 and super creatives of the Arts and Industries. The same can be said of Paul Robeson’s Civil Rights struggles in songs and performances. His is a voice that was internationally acclaimed but dogged by the US government of his time.

With all this in mind, I have chosen one individual whose voice, personality and stand as a civil rights campaigner graced the airwaves and sound barriers. The name Harry Belafonte, a Hollywood film star, born in the USA of Caribbean parentage, has from the entertainment mid 1950’s to date and is inscribed in halls of fame globally. Despite all this, Harry remained the man Caribbean’s called their star boy, a mentor to all colours, creeds and races; someone I have followed from my teenage school days, singing his songs in pubs, restaurants and nightclubs in Britain, Europe, and beyond.

I was in my late teens in the 1950s preparing to leave when Harry came to Grenada to star in the film Island in the Sun, with Dorothy Dandridge, James Mason, Joan Collins, Michael Rennie and others; the first Hollywood film that I knew of, to be shot in Grenada.

For us teenagers, Harry’s presence on screen, his charisma and personality said it all for the boys and girls, for the elder generation and workers of the islands. His songs related to our lives, the culture, drama and economics of Caribbean’s who were looking ahead, searching for meaningful avenues to explore. Education and ambition were the words our parents were singing in our ears daily. Changes were looming to take the Caribbean out of British Colonial bondage and economic strangulation.

I wanted to sing like Harry, forget about looks, there was no chance for anyone to match the good looks of Harry Belafonte. He was the film star (star boy) the girls, the boys, all admired Harry and as for the workers of Jamaica, St Vincent, Dominica, St Lucia and Grenada, the lyric, ‘Come Mr. Tallyman, tally me banana’ and ‘Island in the sun’ were of greater magnitude to many Caribbeans that rivaled anything Elvis Presley or Frank Sinatra sang; Harry’s voice strummed chords that echoed to the melody of our emotions.

‘Day-O’! Even today that call sparks belonging to generations, although when questioning the name of the singer few may know his name and for his huge contribution to the Civil Rights movement in the USA, South Africa, the Caribbean and beyond. His film roles and television success are paths that have inspired me to come to the UK.

At the end of my Grammar School education in 1957 and before leaving my native land Grenada, I became a member of Grenada’s first professional dance and drama group The Bee Wee Ballet Dance Troupe led by Allister Bain. This was the very group that performed the limbo scene in the film ‘Island in The Sun’; filmed in St Georges, the capital of Grenada (GDA). Harry’s starring role in the film was the beginning of a new era. His work inspired me in building my own career in entertainment as a singer, songwriting and educator teaching culture in education to teenagers in St Paul’s (GDA). It is no accident perhaps that I taught and composed similar songs in Britain, Southern Ireland during the Troubles Wales, Denmark, Norway, Germany, Malta and Tenerife, Japan, USA, Belgium and Nigeria.

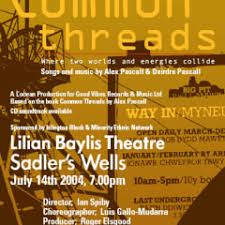

I led in singing Harry’s Banana Boat song and Island in the Sun in GBSS Secondary School’s staging of In the staging of Derek Walcott’s play, ‘The Sea at Dauphin’ in 1957. That performance blossomed into an opportunity of a lifetime with the Bee Wee Ballet Dance Troupe as a drummer and vocalist at the ‘Festival of Arts, 21 April 1958, for the Inauguration of the Federation of the West Indies, sharing those historic moments for change and advancement to a career with a wealth of prospects. Shango, borne out of the folklore traditions encouraged by my mother Doris Pascal and Born To Wander performed by The Ales Pascall Singers, now available on the album Common Threads as a digital download essential elements of the musical play scripts soundtrack.

So, when I got my first job in the UK working on the London Underground (London Transport) alongside getting to meet others who had already began laying paths for those like me who followed, adding Caribbean roots and rhythms as a cultural pioneer in British cultural life, in journalism, education and media communication.

Equipped with the songs Belafonte sang, I charted the night’s performances and singing competitions in pubs across London. IN my experience, the host community loved it because Harry’s film and television image he portrayed paved the path of acceptance for me to benefit from. It was the days of the Irish workers and nurses. West Indians kept the buses and trains running, as young Caribbean men and women had become the ground force of the Transport and National Health Service. The Irish men in particular were largely the road builders and the Irish women also doing their part for the National Health Service (NHS) and the Italian restaurants had the edge in sought after cuisine and customer service with welcoming charm.

In and around London, I was the one and only Black person in 1958 with a conga drum singing Harry’s songs Island in the Sun, The Banana Boat Song (Day-O), Scarlet Ribbons and the calypso Rum and Coca Cola that Harry and the Andrews Sisters had popularized. With the drum and as a tenor, I began writing and singing with measured confidence, determined to follow in Harry’s footsteps, building on my success, shaping it the way I wanted.

Photo: © Good Vibes Records and Music Ltd

Photo: © Good Vibes Records and Music Ltd

As the trains travelled, I hummed and composed to the rhythm of the underground, which has since led me to develop techniques for writing songs and vocal training within lecture/performances. I love London city, and so it is no surprise that I write about London often. Talking with Robert Elms during his show Listed Londoners reminded me of my reminiscences in and around the Thames writing Ferry Boats often performed live when invited to various schools up and down the land.

The Alex Pascall Singers (see the Alex Pascall Media Stack Moment, Lucky Old Sun’ .mov link) also featured on the Common Threads digital mp3 soundtrack, was a group my wife suggested we form to include the range of ethnicities and youth of Diaspora in the UK some of whom are still with us today. Songs included entering a competition with my song, Shake Hands winning the 1973 Malta International Christmas song competition for peace in the world at the Festival of Malta. My work with the BBC began in 1962 performing as a musician blowing the conch shell, a traditional Caribbean past time, which led to storytelling with original Anansi Stories and poetry contributions both on radio and TV. I cherish the works I created alongside Anita Sterner in the 70’s and 80’s and with poet and broadcaster, Michael Rosen both on radio and during the advent of Channel 4 – Happy and progressive times.

With that wealth of knowledge and experience gained from being a pioneering Black presenter and Producer of Black Londoners, an access slot on BBC Radio London and my work as a touring educator in schools across the nation, brought me to the attention of Anne Wood the creator of the early years/pre-school series, Teletubbies. The early creative collaboration with Anne Wood as a consultant to the series (which included choosing schools I worked with to film and introducing multi-cultural representation within the live elements episodes, presentations and perspectives), was enjoyable as was the initial joy associated with the series hitting the scene on British and US television.

In summary all I can say is that I was culturally blessed and lucky, I had someone in Harry Belafonte who was crucial to both areas of the career path I chose, but in so doing my travels to schools, colleges and universities in Britain and beyond has in it traces of Harry Belafonte’s influences. As I look back all I can say is that I was lucky and was privileged to have been given opportunities that I used with the talent that I have and must now in passing them on say a big thank you to Harry Nat King Cole , my wife Joyce and the many that I have encountered in my travel to find the different stages for performance, but Harry Belafonte’s songs, in particular the calypsos, his life as an activist, his work with Miriam Makeba and James Baldwin whom I later interviewed, his understanding of the struggles of the Black and suppressed peoples of the world gave me something to archive and pass on to other generations. Indeed, at the turn of the millennium, I sought guidance on a matter only to find out much later, I had been in communication with a member of your Long Road To Freedom – An Anthology of Black Music team – How I wish I knew at the time – still an ardent Harry Belafonte fan ☺

For the past six decades since my arrival in Britain from the tri islands of Grenada, Carriacou and Petit Martinique, I have journeyed inside and outside of Britain, bringing to my attention, threads of opposition and the undertones of rejection instead of commonalities and colossal contributions to global communities. The Caribbean saying, ‘Come see and come live with me’, have proven that apart from being human beings, the concept of white supremacy has aimed to blind the meaning of the term British, in Britain, contrary to the reasons we left our homelands to come to Britain. The strides we have made do not equal the heavy price we have been paid at the hands of the political, social and economic disadvantages meted out to date. Harry Belafonte lifeworks offer keys and a guiding light that have steered me well.

Thanks to you Harry are in order.

Alex Pascall, O.B.E.

www.goodvibesonline.co.uk